trending: le mont st. michel chore jacket

BY TAVIS GRAY

Everything was bleu. I had open twelve tabs, retail apostles on high, each featuring a hydrone article of clothing I’d shelved for later consideration. Shelved because each was wrong in its own way, stubborn, shining back at me behind degenerative glow. I tucked myself deeper into my hobgoblin posture, pulled up my alternative down comforter, and basked in my distastes. How could everything be so wrong? I was searching for workwear for all gods’ sake. And this was 2019! Jena in HR may pencil skirt herself from nine to five—but at six? At six Jena hits the town in garage coveralls, a beige and formless ode to a clock punched and a gasket greased. If the Jenas of the world could cavort as mechanics, why then couldn’t I find the the right jacket, for the right price, in the right color, and of the right working man’s cut?

I nearly broke my middle finger against the trackpad. There, and in perfectly exposed photography, was the object of my cart’s desire. Le Mont Saint Michel Chore Jacket in Blue. Stitched tightly in durable cotton moleskine. Three patch pockets. Button closure. Unlined. Beautiful, practical, simple, heartbeat skipping, so French, and—draw and quarter me—sold out. Not just on my preferred corner of capitalism’s Internet, but in all corners. I clicked back through my tabs. They had not improved. I dug a nail into the skin of my arm. My golden fleece had appeared before me as an apparition. Made a memory before I could grab it under teeth. I suddenly recalled the fourth act of La Boheme when Mimi is presented with a fur muff. She warms her hands and dies moments later of consumption. At least Mimi got her muff. I signed up for new stock notifications.

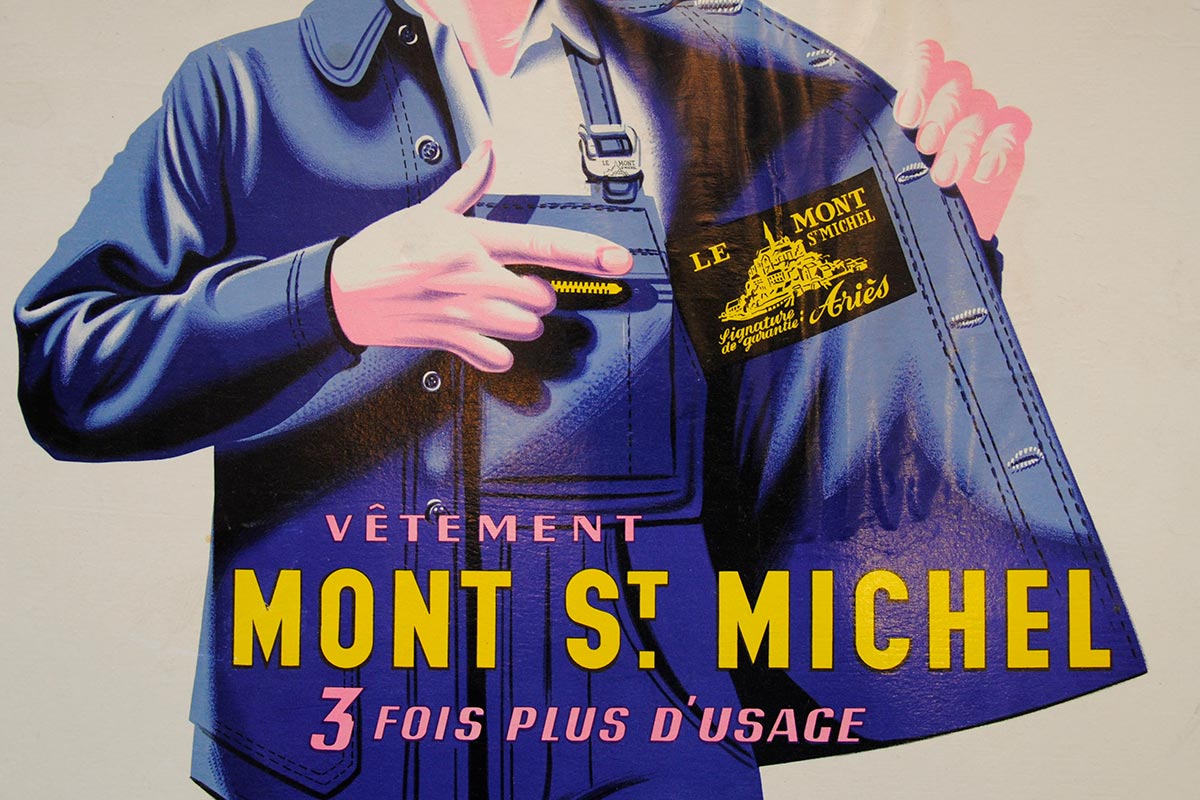

© Le Mont St Michel.

Le Mont Saint Michel (named for the nearby peninsular Abbaye) was started by the Ariés family in Western France in 1913. The work jackets they produced were worn by French craftsmen and farmers as signifiers of their trade for much of the first half of the 20th century. Imitators—or perhaps in the spirit of fraternité: contemporaries—sprang from the land like soldiers from sowed dragon’s teeth. But as with the rest of the world, France urbanized and mechanized, and the need for well-made, washable, patchable farmwear declined. The designer Alexandre Milan took over the Ariés family business in 1998. The brand’s website (and interior label on its jackets) still features the original etching of its eponymous structure. Men and women cursed with heavy upper lips pout their way in and out of “genuine” jackets in colors not just blue, or even navy, but “brick,” “sky,” and “kraft,” which yes, resembles the cheese. I stare into the void of my blue chore jacket. The bolded “UNAVAILABLE” stares back.

In France, the chore jacket is called bleu de travail —“working blues”— denoting not only the uniform’s identification with workers, but its distinction from those who manage those who work. I realize the context in which I’ve attempted purchase: a symbol of the proletariat has become my trendy retail obsession. My thoughts return to Jena and her mechanic’s khaki. Workwear may have recently infiltrated the club, but not the populace. Not the mall.

Jacob Davis (né-america: Youphes), with financial backing from Levi Strauss, filed a patent on May 20th 1873 for “improvements in fastening pocket openings” and began to mass produce the result: our modern blue jean. Davis had been approached three years earlier by a woodcutter who needed a durable pant to, and this must be assumed, cut wood. The result was a creation of fastened duck cloth (durable linen, no feathers, replaced by denim in 1871), which quickly became ubiquitous with railroad labourers in a way that prevented Davis from keeping up with demand. Enter patents, enter factories, enter Daisy Dukes and high-waists, boot cuts, flares, skinnies, and this. There is perhaps no other piece of clothing more saturated in the 20th century than the blue jean. Yves Saint Laurent wished he had invented them, Warhol wanted to die in them (he died, like many, in a hospital gown), and Kelly Clarkson has posited that Texan women exit the womb in a pair.

L: US Patent No. 139, 121. Public Domain. R: A Texan woman.

Blue jeans are not the end-all for fashion’s obsession with workwear, though. A century and change after Jacob Davis and Levi Strauss brought denim to the mass market, Tupac brought overalls to hip-hop. The early 2000s saw an influx of Japanese boro style jackets (another garment borne of worker’s necessities) to high fashion; brands like Visvim and Engineered Garments continue the patch-work today. Tributes to NYC photographer Bill Cunningham’s famous blue chore jacket hit runways not long after his death. Perhaps his is the reason for my hunt. Bought for $20 in a Parisian hardware store, Cunningham’s bleu de travail lasted him a career in streetwear photography. His jacket was as instantly recognizable and stylish as it was utilitarian. The perfect uniform.

The chore jacket haunts me like a phantom limb. On a Friday, I walk from my apartment east into Koreatown. The wind kicks at my bare arms. It pulls at the tote hanging against my right shoulder. I fantasize three deep, tote-killing pockets. I might keep anything within their expanse. I might carry a whole book across my small intestine. The wind dies down. There might be something godly in this phantom.

Around 334 or 354 (what is twenty years, really?), Martin of Tours, as he rode through the gates of Amiens, tore his Roman military cloak (blue) in half so that a beggar (Jesus, when is it not Jesus?), might stay warm through the night. Upon waking, Martin discovered his cloak re-patched and whole. The cloak, considered miraculous, was carried for a time by the king into battle, used to swear oaths, and was passed through the church for centuries, often stored in small, temporary churches named capellas — for “little cloak” — which is where we get the word for “chapel” today.

Martin was later canonized and claims the blue stripe in the Parisian flag, which also claims the equitable stripe in the national tricolour. That blue stands for liberté, but also: the many, the poor, and perhaps for those who rose up at the end of the 18th century with shouts of “...égalité!” It is a socialist’s blue.

You’ll find many old blue books on my bookshelf. One of them, written in 1906 by the Karl Marx biographer John Spargo, remains pertinent today. The Socialists: Who They Are and What They Stand For attempts to answer a curiosity once mused over in the drawing rooms of Spargo’s day and now screamed from red-faced pundits vulpine in ours. Spargo reckons with the perils of capitalist materialism and insists that a worker’s movement correct the mistakes of the utopian socialist models presented and failed of the previous century. He argues for the protection of labor against larger, colluded interests (not without premonition either, see: the anti-trust acts of the next decade); indeed, a windowless statement forms: unregulated competition does not and will not lead to free markets—it leads only to monopoly; suffering. Spargo invokes the thoughts of the Irish reformer James Bronterre O’Brien. We must destroy private ownership of socially necessary goods. A nation of labourers cannot let private property master common life. My two-hundred-and-twenty-five euro chore jacket stands pocket-mouth agape.

L: Bill Cunningham, working. © First Thought Films. R: Paul Newman, working. © Warner Bros. Ent.

In a culture moving iceberg-meltingly fast away from materialism, and as a new generation skirts laissez faire for environmental existentialism, how can we predict anything but a teenage army in their own “working blues,” storming the bastille as Billie Eilish croons revolution in their ears? Even as workwear (and Le Mont St. Michel) tortures me with products perfectly tailored and posh-ironic, I can’t help but wonder if the eventual devolution of luxuries will change my retail-sartorial obsessions—if the Carrie Bradshaw inside me will wither as she selects price: low to high for the thousandth time with a red-eyed and class-trapped tap of search. In search of what?

But then I think again about those three organ-encompassing pockets. I sigh my materialist sigh and tug at the phantom caught against my chest. I button up. I dream of bleu.